Sonya Mmakopano Rademeyer

photo credit:Tegan Fayne

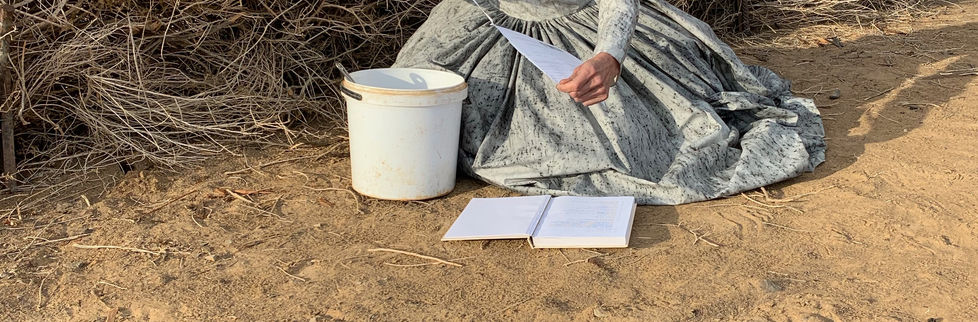

Please forgive me (2019) enacts the state of experience of post-traumatic memory of the politics of land. Using the specific geographical landscape of the remote Tankwa Karoo* to embed a series of short performances, the work is placed within the social history of early colonization when the first European settlers took land from those to whom it belonged to, namely the hunter-gatherer San (Bushmen) and the pastoral Khoekhoe.

Moving from an inside place and a personal position, the work links present to past memories through a series of performance pieces. Initially departing from my own genealogy, I deconstruct the documentation of my ancestral heritage from the form of a book• to that of a paper-mache bowl, later used as an offering of forgiveness to the land. This considered act is a deliberate attempt at stepping out of an inherited history and is a contribute of thought towards the regardless acceptance of inherited Colonial thinking around the historical taking of land.

The various short performance pieces are stitched together in a way that reflect how sense memories – memories that are outside of memory and therefore remain unspeakable - are retained in a fragmented way. Not offering a clear narrative which can be processed in common memory, generally allowing language to translate meaning, the viewer is left to interpret the sensations of the visuals themselves thereby creating an encounter in the present. Using the present within the Tankwa landscape I create rubbings off certain rock surfaces that evoke strong references to hieroglyphics, an ancient pictorial language that points towards complexity and decoding. For me, these rock rubbings are the mark-makings of collective memory pertaining to land, and, although perhaps separated by ethnic groupings, race and time we collectively share these trans-generational memories.

By wearing the mark-making of collective memories as a dress adorning my own body I question what is written in the body: how does the body remember? How does the body – as loci – remember the mapping, processing and translation of the trauma of memory over time? Does it become part of our very fabric? Do our brains get re-wired? Does it change our very DNA? And, how can we alter this patterned (inherited) way of thinking if we do not actively step out of it, as the newly-formed bowl testifies to. Grappling with these and other issues, the Oryx becomes the symbol of this struggle. Linking the inside (local) to the outside (global) space, the entangled Oryx in the fence comes to represent political struggles at large. Fences, belonging in the Tankwa or to Trump’s at the Mexican border do not differ in their directed purpose of separation and division.

Re-enacting the role of the Oryx becoming entangled and dying a slow and painful death through the medium of performance, I attempt to create an understanding of how vulnerability is required in order to make sense of violent history. And, in facing and unpacking our own contributions to violence, we might be able open an enquiry into empathy and ultimately forgiveness.

The final performance testifies to how the fatigue of empathy finally changes the holding space, opening artistic enquiry into how resistance continues to alter cultural history. And, although the title points toward a personal plea for forgiveness, it is ultimately a call for global tolerance.

* Tankwa Karoo is a vast and desolate geographical area within the interior of South Africa.

• Historically documented as 21 April 1751 on arrival of the Schakenbosch ship from Rotterdam (The Netherlands).